In January, a federal court decided California Communities Against Toxics (CCAT) v. Trojan Battery Company in favor of Trojan, a large battery manufacturing facility in industrial Southern California. A federal judge dismissed the case without the ability to amend after plaintiff CCAT failed to meet its burden of satisfying the multiple elements of standing at a bench trial last December.

The defense highlighted the fact that the facility’s point of discharge into the ocean was 13-miles from where the plaintiff’s alleged “injury” occurred. Since multiple other potential pollutant point sources were located along that 13-mile stretch, the facility’s discharge could not be established as the “causation” for the plaintiff’s injury.

The case outcome is instrumental for future stormwater litigation because standing has historically been a low-bar for environmental groups to prove. This post unpacks the basis of the court’s decision and its potential effects on future litigation. It also seeks to explain why standing is so often litigated aggressively and why it can be so hard to challenge from a defendant’s perspective.

Seal Beach, California, where the plaintiff’s alleged injury occurred. Trojan’s facility discharges into the Pacific Ocean 13-miles from Seal Beach.

The Burden of Standing

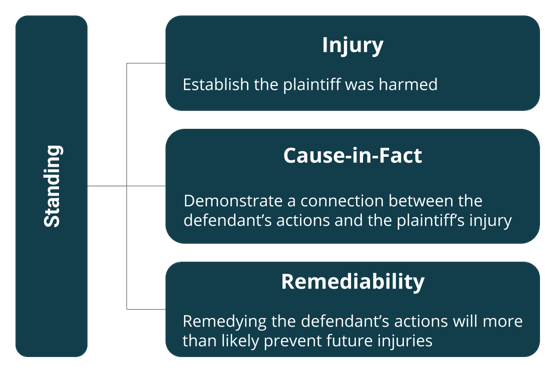

When a citizen suit is filed in court, the plaintiff or environmental group filing the suit bears the burden of proving standing. As a principle, standing involves satisfying three prongs: injury, cause-in-fact, and remediability. Injury must be concrete and imminent, causation must be directly traceable (by substantial likelihood) to defendant’s actions, and it must be more than just ‘likely’ that favorable Court action will remedy the problem.

Since the plaintiff bears the burden of establishing standing, the defense strategy for a citizen lawsuit frequently involves disputing that the environmental group has standing to bring the case. Demonstrating standing is essentially proving that the plaintiff incurred an “injury” from the defendant. For a stormwater citizen lawsuit, this typically involves demonstrating that the environmental group has one or more members who recreationally use the waters where the defendant discharged pollutants.

There are three elements to establishing standing in a citizen lawsuit.

Why is it So Easy for an Environmental Group to Establish “Injury”?

Historically, it has been relatively easy for the plaintiff to prove an “injury” was incurred in Clean Water Act cases. Author and attorney Mark Ryan assessed the role standing plays in litigation in his 2017 article published by the American Bar Association . Ryan argued that although “defendants routinely, and reflexively, move to dismiss on standing grounds, usually trying to prove that the environmental plaintiffs have not established an injury, […] it is clear that Laidlaw established a fairly easy test for showing injury, making it hard for defendants to succeed in challenging citizen standing.”

It is clear that Laidlaw established a fairly easy test for showing injury, making it hard for defendants to succeed in challenging citizen standing.

The seminal case Ryan referred to is Friends of the Earth, Inc. v. Laidlaw Envtl. Servs. (TOC), Inc. , 528 U.S. 167, in which the Supreme Court found that the plaintiff had standing because the defendant’s discharges “directly affected petitioners’ recreational, aesthetic, and economic interests.”

The Court also found that citizen plaintiffs still needed to meet the elements of standing, even if they allege ongoing violations because coming into compliance does not necessarily mean the case is moot . Ryan summarizes the impact of the case by stating that “post- Laidlaw case law demonstrates that plaintiff groups routinely meet the standing requirement by simply alleging that one or more of their members live near and recreate in water affected by defendant’s discharges and are adversely impacted by the defendant’s conduct.”

Summary of CCAT v. Trojan

In California Communities Against Toxics (CCAT) v. Trojan Battery Company , a federal judge dismissed the case without the ability to amend after plaintiff CCAT failed to meet its burden of satisfying the multiple elements of standing at a bench trial last December.

The premise of the decision highlights some of the numerous requirements that an organization must show to bring suit on behalf of members. Specifically, the issue at contest came down to whether the individual members would have had standing to sue in their own ‘right’, or in other words, relied on the individuals behind CCAT to adequately support how they would actually be affected by Trojan Battery Company’s facility potentially discharging zinc and lead into the receiving waters.

Establishing Evidence of ‘Injury’

To establish injury, individual plaintiff and community member Mr. Marquez provided an evidentiary declaration of facts that began with his investigation of the Defendant’s facility as a frequent user of the Coyote Creek, which drains into the San Gabriel River and nearby ocean at Seal Beach, where he swims and fishes.

Citing Lujan and Ecological Rights Foundation, this evidence was enough to establish sufficient connection to support injury within standing on the basis that actual injury was not necessary but rather, an ‘increased risk of harm’ was suitable. Interestingly, the court agreed that the plaintiff was not even required to show quantifiable discharges in lead and zinc from Trojan Battery. However, the pivotal argument made by Defendant contesting ‘injury’ functioned around Mr. Marquez’s use of the adjacent Coyote Creek trail as a bicycle path rather than engagement with the water of the river itself, thus there was no “direct” harm to his use of the Coyote Creek trail.

Examining the Evidence for ‘Causation’

Next, the court looked at physical evidence in the form of prior reports to determine ‘causation’. For one, the permit limit exceedance figures obtained from monitoring reports did not help in convincing the court.

Not only did they look to the 2014 and 2016 “California 303(d) List of Water Quality Limited Segments” which stated that zinc and lead were not impairing Seal Beach, the ten-year-old TMDL only reflected high levels of copper in the surrounding river and its immediate creeks, suggesting that the potential point source pollution from the facility did not actually reach the claimed injury area.

See our post on the California Toxics Rule for an explanation of the role of water quality limits in citizen lawsuits. In addition, the Defendant’s expert witness testified that stormwater travels from the facility through the municipal storm system before emptying into the Pacific Ocean, nearly 13 miles from where Mr. Marquez alleged the accumulation of lead and zinc in stormwater starts.

The Nuanced Role of Distance in Causation

The Court also compared the facts of this case with a very similar one, Ecological Rights Foundation v. Pac Lumber , 230 F.3d at 1146 (1999) in which the distance from the timber facility’s alleged dumping in the water body was similarly removed upstream from the location of the alleged contamination. Distinguishably, the court in the CCAT vs. Trojan case found that the 13 miles separating the point source to Mr. Marquez’s ‘injury’ severely impacted the traceability argument to uphold causation.

Given the extra distance (by 1 mile?) in the case, the Court felt that the attenuation was too extreme, despite the liberal burden of proof needed by plaintiffs. It remains a mystery how the court reasoned the mile difference to be “significantly” greater without explaining their rationale. However, the court did not discuss redressability because causation was not satisfied. In sum, the Court was convinced that because the number of intervening other point sources of pollution existed along the 13 mile stretch of ocean, the Plaintiff was unable to satisfy causation since the facility’s pollution only could end up at the point in Seal Beach where the alleged injury occurred.

So When Should I File a ‘Motion to Dismiss’ for Lack of Standing?

While a successful challenge to statutory standing at best results in a dismissal with prejudice, there are a few practical considerations that should be taken into account. For one, since a Court will resolve a standing issue in the same way as any other issue that can be raised on a motion to dismiss, it will essentially accept the plaintiff’s allegations as true.

However, waiting until the summary judgment phase to raise a standing issue, both parties will have engaged in costly litigation that could have been foreseeably avoided. In summary, while the decision in the CCAT v. Trojan case may have slightly raised the bar for environmental groups to prove causation and standing, the bar was very low to begin with.

With mandatory eReporting driving publicly accessible compliance documents, environmental groups typically have more than enough documentation to prove standing in a citizen lawsuit given adequate preparation.

Even when a ‘Motion to Dismiss’ for lack of standing is granted (the odds are against facilities), litigation costs will be significant to reach that point. However, while citizen lawsuits may seem random, there are a few steps companies can take to digitally track their compliance and significantly reduce the risk of being targeted by an environmental group.